The GDPRD co-organized a virtual roundtable with the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) and the European Commission, in collaboration with the UN Food Systems Coordination Hub, on “Reshaping Food Systems Financing in a Crisis and Post-Crisis Environment: Driving Donors’ Commitments” on 29 September, 2022.

The event, which followed Chatham House rules, provided an open space for donors and other organizations to discuss critical challenges and opportunities for reorienting food systems financing efforts in a shifting development landscape and to understand where financing gaps currently exist. The conversation built off of the last donor roundtable held on 20 May 2022, titled “Addressing the Impacts of the War in Ukraine on 3F (Food, Fuel, Fertilizer) Prices for Rural Small-Scale Producers”.

Over the last three years, the number of hungry people has been continuously rising. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World (SOFI) 2022 found that between 702 and 828 million people face hunger globally, an additional 150 million since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2019. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is expected to worsen global food insecurity by another 19 million people. The multiple crises highlight global food systems’ fragility and the need for radical transformation.

The Food Finance Architecture, launched during the 2021 Food Systems Summit, assessed that moving to high-performing food systems by 2030 requires an approximate additional US$300-350 billion in investments per year. However, the world economy loses approximately US$12 trillion annually in hidden environmental, social and economic costs because of how food systems operate – translating to 30 times the amount required for food systems transformation. The fiscal target to achieving food systems transformation, albeit reachable, is not being met. Food has become the next major generational challenge we face today, and a paradigm shift in financing is critical in transitioning toward healthy, sustainable and just food systems. The roundtable started the conversation on what exactly this paradigm shift entails and how to move financing forward in unprecedented times.

Key points highlighted by participants included:

Data, accountability and transparency for evidence-based decisions

- Even if the international community manages to mobilize the financial resources needed, a major challenge will be being able to allocate them properly.

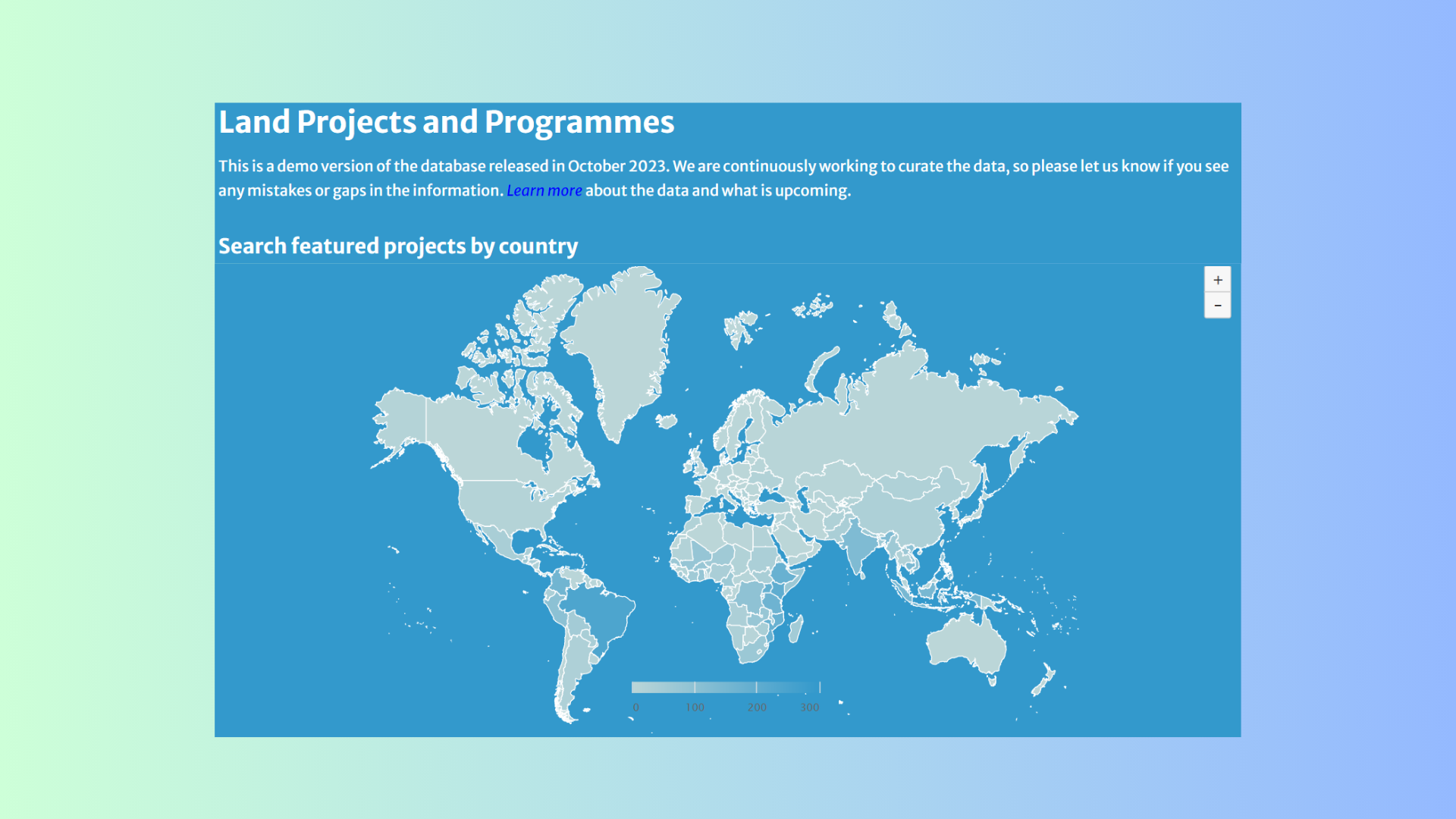

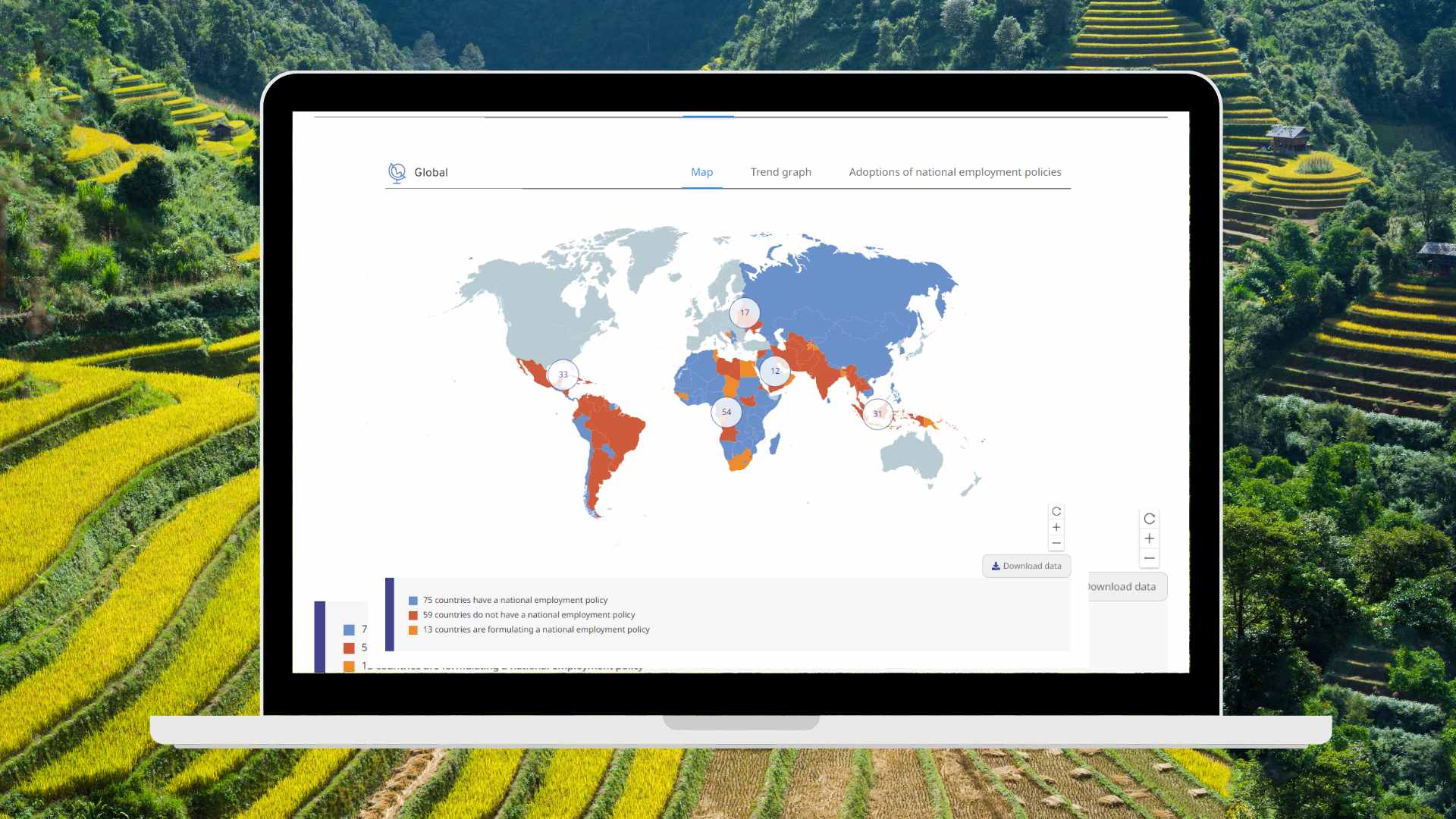

- There is a need to quantify precisely how much money is being financed for food systems and where it is being allocated to make evidence-based decisions. Participants discussed the usefulness of budgeting tools and transformation trackers to help governments, donors, food businesses and civil society organizations assess the performance of country food financing architectures. Such devices could identify risks, manage public investments and incentives and flag the need for change in financing decisions.

- A broad set of indicators should be established to evaluate synergies and trade-offs of both short and long-term projects being funded.

- More and better R&D in food and agriculture is necessary for establishing such tools and indicators and will benefit food systems in the long term.

- Accountability and transparency are essential from all stakeholders for transformative financing measures to be impactful.

Taking a long-term investment perspective and reshaping public support

- Future crises are inevitable, and we must invest in long-term resilience building to enable structural change. We can no longer afford to follow a typical short-term crisis response cycle; we must handle trade-offs between short-term benefits and long-term approaches, while managing risks – there is no win-win situation.

- Official Development Assistance (ODA) has been the primary source of development cooperation finance, but other factors such as agricultural policies have also influenced the donor environment with changes enacted in recent years. For example. under the Ministerial Decision on Export Competition adopted in Nairobi in 2015[1], World Trade Organization members eliminated export subsidies to reduce trade distortions that lead to production surpluses on international markets, lowering international prices and reducing small producers’ competitive ability.

- One panelist pointed out that certain country-level agricultural policies make food artificially more expensive to increase farmers’ incomes which end up hurting domestic consumers. Encouraging countries to revise agricultural policies and better align their incentives is one solution to allocating funds more effectively. Coherence is needed across development, trade and support policies to avoid diverging interests.

- A major call was the need to break the cycle of subsidies that negatively affect market prices, are environmentally destructive, and harm small-scale producers and Indigenous Peoples. Financial incentives should be better targeted and regulated, and agricultural policies should be focused toward the root of problems.

- Capacity-building can encourage a shift from aid dependency to long-term resilience, and can give communities the tools to influence their own realities.

- Participants stressed the need to rebalance power in supply chains. Supporting local producers, especially in a way that enhances local consumption rather than export markets, can improve access to affordable, healthy diets while boosting biodiversity and wages. Investment is currently lacking for small-scale, local initiatives and crops when compared to international export production, and de-risking private sector investment in this area can be beneficial for the long term.

The nexus of food and health

- The food and agriculture sector can take inspiration from the health sector on how they rallied resources during the COVID-19 pandemic by mobilizing money through private-sector and market-based approaches. While innovative financing techniques may be beneficial, participants emphasized that they should not overcome public funding.

- Participants discussed potential lessons from the health sector’s success in public-private partnerships and public development during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Donors engaging in agriculture and food security can take inspiration from the health sector in using blended finance[2], de-risking[3], and guarantee funds[4]. However, private sector financing must align with environmental, social and health targets. Food businesses must be held accountable with measurable targets on greenhouse gas reduction, nutrition and living wages in order to have a sustainable and just food system.

Summary

A fundamental change is required in how the donor community makes investments as catalytic and transformative as possible. Working in unison is essential for responding to an escalating food crisis and shaping the way for a sustainable future at global and local levels. The participants emphasized the need for a food systems approach with a long-term perspective and accountability from all stakeholders moving forward. Participants acknowledged that this is just the beginning of discussions on this important topic; the GDPRD roundtables will continue to serve as an open space for informal dialogue around emerging issues.

Footnotes

[1] WTO | TENTH WTO MINISTERIAL CONFERENCE, NAIROBI, 2015 – Tenth WTO Ministerial Conference – Nairobi

[2] Blended finance is the strategic use of development finance for the mobilisation of additional finance towards sustainable development in developing countries. Blended finance attracts commercial capital towards projects that contribute to sustainable development, while providing financial returns to investors. Source: OECD.

[3] ODA is used to adjust the risk-return profile to facilitate investment in projects that would not have otherwise received finance. As a recent Overseas Development Institute (ODI) (2019) Report describes: ‘Official development finance is used to provide a subsidy to bring the risk-adjusted rate of return in line with the market, increasing the allure of the investment from a private commercial investor perspective’ Source: Attridge and Engen 2019, p 26. Policy Department for External Relations Directorate General for External Policies of the Union PE 603.486 – May 2020

[4] A guarantee fund provides a loan or credit guarantee, i.e. it enables a borrower to approach a bank for a loan. Guarantees are particularly useful for borrowers who do not have sufficient collateral, such as land or other assets. Small borrowers almost always lack (sufficient) collateral. Therefore, the purpose of loan guarantee schemes is to share the credit risk with the bank. Source: International Labour Organization (ILO).